China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

"Around the World of a Bicycle - Cycling through China in 1886 "

Part 1

Cycling through China - Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part7 | Part 8 | Around the World on a Bicycle - Maps and Pictures

Around the World

on a Bicycle

1884- 1886

By Thomas Stevens

PREFACE.

Shakespeare says, in All's Well that Ends Well, that "a good traveller is something at the latter end of a dinner;" and I never was more struck with the truth of this than when I heard Mr. Thomas Stevens, after the dinner given in his honor by the Massachusetts Bicycle Club, make a brief, off-hand report of his adventures. He seemed like Jules Verne, telling his own wonderful performances, or like a contemporary Sinbad the Sailor. We found that modern mechanical invention, instead of disenchanting the universe, had really afforded the means of exploring its marvels the more surely. Instead of going round the world with a rifle, for the purpose of killing something, - or with a bundle of tracts, in order to convert somebody, - this bold youth simply went round the globe to see the people who were on it; and since he always had something to show them as interesting as anything that they could show him, he made his way among all nations.

What he had to show them was not merely a man perched on a lofty wheel, as if riding on a soap-bubble; but he was also a perpetual object-lesson in what Holmes calls "genuine, solid old Teutonic pluck." When the soldier rides into danger he has comrades by his side, his country's cause to defend, his uniform to vindicate, and the bugle to cheer him on; but this solitary rider had neither military station, nor an oath of allegiance, nor comrades, nor bugle; and he went among men of unknown languages, alien habits and hostile faith with only his own tact and courage to help him through. They proved sufficient, for he returned alive.

I have only read specimen chapters of this book, but find in them the same simple and manly quality which attracted us all when Mr. Stevens told his story in person. It is pleasant to know that while peace reigns in America, a young man can always find an opportunity to take his life in his hand and originate some exploit as good as those of the much-wandering Ulysses. In the German story "Titan," Jean Paul describes a manly youth who "longed for an adventure for his idle bravery;" and it is pleasant to read the narrative of one who has quietly gone to work, in an honest way, to satisfy this longing.

THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON.

CAMBRIDGE, MASS., April 10, 1886 .

[Note: This contains only the China portion of Thomas Stevens' trip. For the complete etext see the Gutenburg Project.]

Around the World

on a Bicycle

CHAPTER XVII.

THROUGH CHINA.

Daily rains characterize our voyage from Singapore through the China Sea-rather unseasonable weather, the captain says; and for the second time in his long experience as a navigator of the China Sea, St. Elmo's lights impart a weird appearance to the spars and masts of his vessel. The rain changes into misty weather as we approach the Ladrone Islands, and, emerging completely from the wide track of the typhoon's moisture-laden winds on the following morning, we learn later, upon landing at Hong-kong, that they have been without rain there for several weeks.

It is my purpose to dwell chiefly on my own experiences, and not to write at length upon the sights of Kong-kong and Canton; hundreds of other travellers have described them, and to the average reader they are no longer unique. Several days' delay is experienced in obtaining a passport from the Viceroy of the two Quangs, and during the delay most of the sights of the city are visited. The five-storied pagoda, the temple of the five hundred genii, the water-clock, the criminal court-where several poor wretches are seen almost flayed alive with bamboos-flower-boats, silk, jade-stone, ivory-carving shops, temple of tortures, and a dozen other interesting places are visited under the pilotage of the genial guide and interpreter Ah Kum.

The strange boat population, numbering, according to some accounts, two hundred thousand people, is one of the most interesting features of Canton life. Wonderfully animated is the river scene as viewed from the balcony of the Canton Hotel, a hostelry kept by a Portuguese on the opposite bank of the river from Canton proper.

The consuls and others express grave doubts about the wisdom of my undertaking in journeying alone through China, and endeavor to dissuade me from making the attempt. Opinion, too, is freely expressed that the Viceroy will refuse his permission, or, at all events, place obstacles in my way. The passport is forthcoming on October 12th, however, and I lose no time in making a start.

Thirteen miles from Canton I reach the city of Fat-shan. Five minutes after entering the gate I am in the midst of a crowd of struggling, pushing natives, whose aggressive curiosity renders it extremely difficult for me to move either backward or forward, or to do augit but stand and endeavor to protect the bicycle from the crush. They seem a very good- natured crowd, on the whole, and withal inclined to be courteous, but the pressure of numbers, and the utter impossibility of doing anything, or prosecuting my search for the exit on the other side of the city, renders the good intentions of individuals wholly inoperative.

With perseverance I finally succeed in extricating myself and following in the wake of an intelligent-looking young man whom I fondly fancy I have enlightened to the fact that I am searching for the Sam-shue road. The crowd follow at our heels as we tread the labyrinthine alleyways, that seem as interminable as they are narrow and filthy. - Every turn we make I am expecting the welcome sight of an open gate and the green rice-fields beyond, when, after dodging about the alleyways of what seems to be the toughest quarter of the city, my guide halts and points to the closed gates of a court.

It now becomes apparent that he has been mistaken from the beginning in regard to my wants: instead of taking me to the Sam-shue gate, he has brought me to some kind of a house. "Sam-shue, Sam-shue," I explain, making gestures of disapproval at the house. The young man regards me with a look of utter bewilderment, and forthwith betakes himself off to the outer edge of the crowd, henceforth contenting himself to join the general mass of open-eyed inquisitives. Another attempt to again enlist his services only results in alienating his sympathies still further: he has been grossly taken in by my assumption of intelligence. Having discovered in me a jackass incapable of the Fat-shan pronunciation of Sam-shue, he retires on his dignity from further interest in my affairs.

Female faces peer curiously through little barred apertures in the gate, and grin amusedly at the sight of a Fankwae, as I stand for a few minutes uncertain of what course to pursue. From sheer inability to conceive of anything else I seize upon a well-dressed youngster among the crowd, tender him a coin, and address him questioningly- "Sam-shue lo. Sam-shue lo." The youth regards me with monkeyish curiosity for a second, and then looks round at the crowd and giggles. Nothing is plainer than the evidence that nobody present has the slightest conception of what I want to do, or where I wish to go. Not that my pronunciation of Sam-shue is unintelligible (as I afterward discover), but they cannot conceive of a Fankwae in the streets of Fat-shan inquiring for Sam-shue; doubtless many have never heard of that city, and perhaps not one in the crowd has ever been there or knows anything of the road. As a matter of fact, there is no "road," and the best anyone could do would be to point out its direction in a general way. All this, however, comes with after-knowledge.

Imagine a lone Chinaman who desired to learn the road to Philadelphia surrounded by a dense crowd in the Bowery, New York, and uttering the one word "Phaladilfi," and the reader gains a feeble conception of my own predicament in Fat-shan, and the ludi-crousness of the situation. Finally the people immediately about me motion for me to proceed down the street.

Like a drowning man, I am willing to clutch wildly even at a straw, in the absence of anything more satisfactory, and so follow their directions. Passing through squalid streets occupied by loathsome beggars, naked youngsters, slatternly women, matronly sows with Utters of young pigs, and mangy pariahs, we emerge into the more respectable business thoroughfares again, traversing streets that I recognize as having passed through an hour ago. Having brought me here, the leaders in the latest movement seem to think they have accomplished their purpose, leaving me again to my own resources.

Yet again am I in the midst of a tightly wedged crowd, helpless to make myself understood, and equally helpless to find my own way. Three hours after entering the city I am following-the Fates only know whither-the leadership of an individual who fortunately "sabes" a word or so of pidgin English, and who really seems to have discovered my wants. First of all he takes me inside a temple-like building and gives me a drink of tea and a few minutes' respite from the annoying pressure of the crowds; he then conducts me along a street that looks somewhat familiar, leads me to the gate I first entered, and points triumphantly in the direction of Canton!

I now know as much about the road to Sam-shue as I did before reaching Fat-shan, and have learned a brief lesson of Chinese city experience that is anything but encouraging for the future. The feeling of relief at escaping from the narrow streets and the garrulous, filthy crowds, however, overshadows all sense of disappointment. The lesson of Fat-shan it is proposed to turn to good account by following the country paths in a general course indicated by my map from city to city rather than to rely on the directions given by the people, upon whom my words and gestures seem to-be entirely thrown away.

For a couple of miles I retraverse the path by which I reached Fat-shan before encountering a divergent pathway, acceptable as, leading distinctly toward the northwest. The inevitable Celestial is right on hand, extracting no end of satisfaction from following, shadow-like, close behind and watching my movements. Pointing along the divergent northwest road, I ask him if this is the koon lo to Sam-shue; for answer he bestows upon me an expansive but wholly expressionless grin, and points silently toward Canton. These repeated failures to awaken the comprehension of intelligent-looking Chinamen, or, at all events, to obtain from them the slightest information in regard to my road, are somewhat bewildering, to say the least. So much of this kind of experience crowded into the first day, however, is very fortunate, as awakening me with healthy rudeness to a realizing sense of what I am to expect; it places me at once on my guard, and enables me to turn on the tap of self-reliance and determination to the proper notch.

Shaking my head at the almond-eyed informant who wants me to return to Canton, I strike off in a northwesterly course. The Chinaman grins and chuckles humorously at my departure, as though his risibilities were probed to their deepest depths at my perverseness in going contrary to his directions. As plainly as though spoken in the purest English, his chuckling laughter echoes the thought: "You'll catch it, Mr. Fankwae, before you have gone very far in that direction; you'll wish you had listened to me and gone back to 'Quang-tung.'"

The country is a marvellous field-garden of rice, vegetables, and sugar- cane for some miles. The villages, with their peculiar, characteristic Chinese architecture and groves of dark bamboo, are striking and pretty. The paths seem to wind about regardless of any special direction; the chief object of the road-makers would appear to have been to utilize every little strip of inferior soil for the public thoroughfare wherever it might be found. A scrupulous respect for individual rights and the economy of the soil has resulted in adding many a weary mile of pathway between one town and another. To avoid destroying the productive capacity of a dozen square yards of alluvial soil, hundreds of people are daily obliged to follow horseshoe bends around the edges of graveyards that after two hundred paces bring them almost to within jumping distance of their first divergence.

Occasionally the path winds its serpentine course between two tall patches of sugar-cane, forming an alleyway between the dark-green walls barely wide enough for two people to pass. Natives met in these confined passages, as isolated from the eyes of the world as though between two walls of brick, invariably recoil a moment with fright at the unexpected apparition of a Fankwae; then partially recovering themselves, they nimbly occupy as little space as possible on one side, and eye me with suspicion and apprehension as I pass.

Great quantities of sugar-cane are chewed in China, both by children and grown people, and these patches grown in the rich Choo-kiang Valley for the Fat-shan, Canton, and Hong-kong markets are worth the price of a day's journeying to see. So marvellously neat and thrifty are they, that one would almost believe every separate stalk had been the object of special care and supervision from day to day since its birth; every cane- garden is fenced with neat bamboo pickets, to prevent depredation at the hands of the thousands of sweet-toothed kleptomaniacs who file past and eye the toothsome stalks wistfully every day.

After a few miles the hitherto dead level of the valley is broken by low hills of reddish clay, and here the stone paths merge into well-beaten trails that on reasonably level soil afford excellent wheeling. The hillsides are crowded with graves, which, instead of the sugar-loaf "ant hillocks" of the paddy-fields, assume the traditional horseshoe shape of the Chinese ancestral grave. On the barren, gravelly hills, unfit for cultivation, the thrifty and economical Celestial inters the remains of his departed friends. Although in making this choice he is supposed to be chiefly interested in securing repose for his ancestors' souls, he at the same time secures the double advantage of a well-drained cemetery, and the preservation of his cultivable lands intact. Everything, indeed, would seem to be made subservient to this latter end; every foot vol. ii-24. of productive soil seems to be held as of paramount importance in the teeming delta of the Choo-kiang.

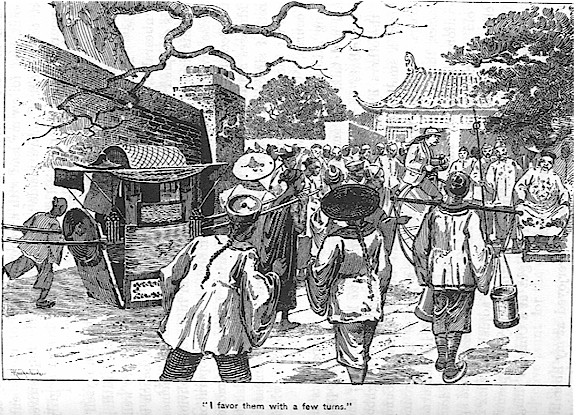

Beyond the first of these cemetery hills, peopled so thickly with the dead, rise the tall pawn-towers of the large village of Chun-Kong-hoi. The natural dirt-paths enable me to ride right up to the entrance-gate of the main street. Good-natured crowds follow me through the street; and outside the gate of departure I favor them with a few turns on the smooth flags of a rice-winnowing floor. The performance is hailed with shouts of surprise and delight, and they urge me to remain in Chun-Kong-hoi all night.

An official in big tortoise-shell spectacles examines my passport, reading it slowly and deliberately aloud in peculiar sing-song tones to the crowd, who listen with all-absorbing attention. He then orders the people to direct me to a certain inn. This inn blossoms forth upon my as yet unaccustomed vision as a peculiarly vile and dingy little hovel, smoke- blackened and untidy as a village smithy. Half a dozen rude benches covered with reed mats and provided with uncomfortable wooden pillows represent what sleeping accommodations the place affords. The place is so forbidding that I occupy a bench outside in preference to the evil- smelling atmosphere within.

As it grows dark the people wonder why I don't prefer the interior of the dimly lighted hittim. My preference for the outside bench is not unattended with hopes that, as they can no longer see my face, my greasy- looking, half-naked audience would give me a moment's peace and quiet. Nothing, however, is further from their thoughts; on the contrary, they gather closer and closer about me, sticking their yellow faces close to mine and examining my features as critically as though searching the face of an image. By and by it grows too dark even for this, and then some enterprising individual brings a couple of red wax tapers, placing one on either side of me on the bench.

By the dim religious light of these two candles, hundreds of people come and peer curiously into my face, and occasionally some ultra-inquisitive mortal picks up one of the tapers and by its aid makes a searching examination of my face, figure, and clothes. Mischievous youngsters, with irreligious abandon, attempt to make the scene comical by lighting joss-sticks and waving bits of burning paper.

The tapers on either side, and the youngsters' irreverent antics, with the evil-spirit-dispersing joss-sticks, make my situation so ridiculously suggestive of an idol that I am perforce compelled to smile. The crowd have been too deeply absorbed in the contemplation of my face to notice this side-show; but they quickly see the point, and follow my lead with a general round of merriment. About ten o'clock I retire inside; the irrepressible inquisitives come pouring in the door behind me, but the hittim-keeper angrily drives them out and bars the door.

Several other lodgers occupy the room in common with myself; some are smoking tobacco, and others are industriously "hitting the pipe." The combined fumes of opium and tobacco are well-nigh unbearable, but thera is no alternative. The next bench to mine is occupied by a peripatetic vender of drugs and medicines. Most of his time is consumed in smoking opium in dreamy oblivion to all else save the sensuous delights embodied in that operation itself. Occasionally, however, when preparing for another smoke, he addresses me at length in about one word of pidgin-English to a dozen of simon-pure Cantonese. In a spirit of friendliness he tenders me the freedom of his pipe and little box of opium, which is, of course, "declined with thanks."

Long into the midnight hours my garrulous companions sit around and talk, and smoke, and eat peanuts. Mosquitoes likewise contribute to the general inducement to keep awake; and after the others have finally lain down, my ancient next neighbor produces a small mortar and pestle and busies himself pounding drugs. For this operation he assumes a pair of large, round spectacles, that in the dimly lighted apartment and its nocturnal associations are highly suggestive of owls and owlish wisdom. The old quack works away at his mortar, regardless of the approach of daybreak, now and then pausing to adjust the wick in his little saucer of grease, or to indulge in the luxury of a peanut.

Such are the experiences of my first night at a Chinese village hittim; they will not soon be forgotten.

The proprietor of the hittim seems overjoyed at my liberality as I present him a ten-cent string of tsin for the night's lodging. Small as it sounds, this amount is probably three or four times more than he obtains from his Chinese guests.

Next: Cycling through China - Part 2

Cycling through China - Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part7 | Part 8 | Around the World on a Bicycle - Maps and Pictures

Bike China Adventures, Inc.

Home | Guided Bike Tours | Testimonials |

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, Inc., 1998-2012. All rights reserved.