China Cycling Travelogues

Do you have a China cycling travelogue you would like

to share here?

Contact us for details.

Pete Richards

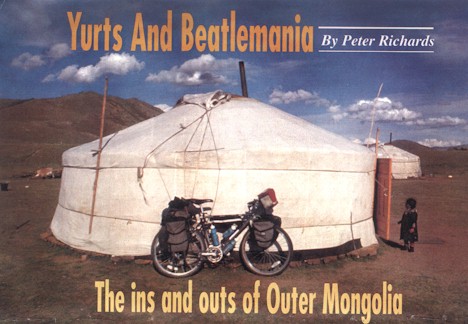

"Yurts and Beatlemania"

The ins and outs of Outer Mongolia

Copyright © Pete Richards, 2001

Mongolia, before 1990 a staunch Stalinist state, which never took kindly to glasnost or peristroika, lifted its curtain to Western tourists in 1991. The country, whose people are closely related to Tibetans and whose pre-Lenin allegiance was to the Dalai Lama, has lone held a fascination for me. So I arranged for a visa immediately upon hearing that Mongolia, no longer a 'Peoples Republic of," had opened an embassy in Washington.

I combined the trip to Mongolia with a longer trip in China, which included riding through Inner Mongolia (a part of China, distinct from the separate country of Mongolia. which is sometimes referred to as Outer Mongolia) to the border town of Erlianhot. There the road degenerates into barely discernible tracks in the sand, and I switched to railroad tracks for the remaining 700 km to the capital of Ulan Bator. On the train a benefactor had no trouble convincing me it would be more comfortable and cheaper to stay at his apartment than in one of the city's overpriced hotels. He also produced a map that, unlike mine, showed which roads are paved and which are camel trails.

Following his advice, I first biked 70 km from Ulan Bator to the resort area of Terelj whose main attraction for Westerners is a camp of tourist yurts. These circular frame tents are the trademarks of Mongolian living. They have largely disappeared in Chinese-dominated Inner Mongolia, but are numerous in (Outer) Mongolia. Even Ulan Bator, otherwise a city of modern high-rises, has a suburban tract where yurts adjoin brick houses. This, my host said in all seriousness, is where the truly rich live. Nothing can beat a yurt for sleeping comfort, so the wealthy have it both ways by retiring from their VCR's and microwave ovens to an ancestral environment.

Since Mongolians are noted for their hospitality, no one with an independent spirit needs to ride a tour bus to Terelj for visiting a yurt. But the ride, which follows the Tuul River east from Ulan Bator, is nonetheless worthwhile. High-rises soon disappear in favor of rolling grassland frequented with yurts, sheep and horses. One herdsman treated me to a glass of kumis, the fermented mare? milk. It tasted like weak vodka and had no apparent effect until I began to see dinosaurs after starting down the road. They proved to be "real," however, belonging to a dinosaur park with realistic life-size statues. The dinosaurs were all the more impressive for having no advertising or concession stands marring the view, a clear indication that Mongolian tourism has not reached the high standards of Western Tackyism.

Terelj is in a forested mountain area, which, it being September, was devoid of mid-summer visitors. Aside from the tourist yurts, much less interesting than the authentic herdsmen yurts, the town consists mainly of an old hotel surrounded by bushes loaded with ripe currants. The latter was more promising than anything on the hotel's menu, and, for the only time in Mongolia. I got the daily requirement of vitamin C.

Further on was a village of yurts where I managed to find food and lodging. Slipper was the Mongolian staple of lamb and noodles, which are eaten at least three times a day. The only variation experienced during the trip was potatoes substituted for noodles. Any-thing green is considered unhealthy. Sometimes carbohydrates and plates are dispensed with altogether. A memorable meal consisted of a shank of lamb and hunting knife being passed around for guests to take their turns. What the food lacks in variety, it does make up for in taste and freshness. Mongolian lamb is acknowledged to be the world's best.

For the first night on the road, I put my sleeping bag on the blanketed floor and slept with family members at the yurt in the village where I had stopped. This privilege cost an inflated 50 turgiks (about one dollar). Other nights the modus operandi was to pitch my one-man Sierra Designs yurt next to a family yurt where I was given food. The usual price was a small plastic bottle of Chinese firewater. As suggested by an Inner Mongolian travel agent, I had purchased 20 for seven cents each before crossing the border and somehow found extra room in the packed saddle bags. They were welcome and quickly consumed gifts. Offers of 10 turgiks (20 cents) were often made for a second bottle, which could have turned a tidy profit.

The return to Ulan Bator took a leisurely two days to allow for a full afternoon of relaxation on the peaceful banks of the Tuul not far from a yurt whose occupants had an ample supply of kumis. Tours that finish in a city are invariably celebrated by stopping at the first good restaurant and gorging on fine food. But if the city is Ulan Bator, it's better to stay in the country. As with Russia, food products never seem to make their way from farm to city. There are long lines of people waiting to buy such luxury items as cabbage and bread, and even longer ones at restaurants and cafes, which could never be accused of imitating Paris. The menus, however, offer more choice than in the country. In the city, one can have lamb with noodles or noodles with lamb. On festive occasions, cold sausage also may be available. After deciding that queuing for an hour wasn't worth it, even though it appeared to be a festive occasion, I broke a vow to be less of an imposition on my host, and reached his apartment in time for lunch. His gracious wife had prepared my favorite-lamb and noodles.

The next itinerary called for an overnight train 311 km north to Suhbataar, last stop on the Trans-Siberian route before what at that time was the Soviet Union, arid then taking three or four days to bike back to Ulan Bator. This train did not have a baggage ear, so my ever helpful and resourceful host persuaded the lady conductor to allow my bike to stand in the aisle of the sleeping car. But after a while she decided this was too much of an obstruction and insisted it go inside the four-bed compartment. It just tit in the space between the two lower berths, which would be fine until someone wanted to get out of bed. My two young roommates had a better idea. Without giving me a chance to raise questions of safety, they hoisted it precariously onto the vacant upper berth. Though I should have volunteered to exchange berths with the bike, it was simpler to secure it with bungie cords,

which one should never leave home without. All this was observed and tolerated by the conductress, who could well have demanded the price of a second ticket.

The train arrived at 5:00 a.m. in darkness and cold rain, hardly an auspicious beginning. There was no Dunkin Donuts in sight, but at least the waiting room was open and there were a number of people with nothing better to do than cheer up a Westerner. At 10:00, one of them led me upstairs to the restaurant, which had just opened and thrust ten turgiks in my hand, more than enough to cover the meal. T protested that, in spite of the way I must have looked, I really wasn't homeless only lost and miserable and showed a wallet full of the worthless currency to prove it. But, as happened commonly, I was considered a guest who should not be insulted by having to pay. The restaurant was less depressing (the highest praise which can be bestowed upon a Mongolian eatery) than any in Ulan Bator, and the lamb and noodles were mixed in a welcomed hot soup.

My spirits brightened even more as the sky started to brighten, and by noon the weather was promising enough to hit the road. As the crowd gave me an enthusiastic sendoff, a woman photographer snapped feverishly from every angle and offered 20 turgiks for the privilege. Passing up this opportunity for a lucrative modeling career, I pedaled away with her running after for a final action shot. So great was my own enthusiasm that I zipped past a turnoff to the south and didn't realize the mistake until confronted 25 km later by Russian Byzantine buildings and border guards who sent me back while laughing at my lack of orienteering skills. I laughed too, once it dawned on me that, with more careful planning, I would have taken the scenic detour on purpose.

The next day I had an encounter with a rock music group. By now I was used to being stopped by passing motorists who were motivated by a mixture of curiosity and generosity; but six wandering minstrels was something different. With aid of a Russian-English dictionary, I learned they had been performing in Suhbataar, and were on the way back to Darkhan, the country's second largest city. In keeping with Mongolia's rapid entry into the 20th century, but not quite the 1990's, their role models were the Beatles. My host's eight-year-old son in Ulan Bator is more current. When told I was American, he brightened up and said "Michael Jackson!" to which I replied, reflecting more refined taste, "Michael Jordan!"

One of the Darkhan group brought out a guitar and the grasslands vibrated with Mongolian-Liverpool sound. Only the goading of the impatient driver finally got them back into the van. Before reluctantly getting on board, the extroverted drummer begged me to meet his wife and child and stay overnight at their apartment in the suburb of New Darkhan, about 15 km away.

I was led to the address of Mongolia's Ringo Starr by a man on a western-style ten-speed who was eager to examine my bike and equipment, particularly the water bottles which so caught his fancy he wanted to buy one. He entered the old but sturdy apartment building and returned with an ecstatic Ringo. The three of us hoisted my loaded bike up the five flights of stairs and crammed it into a corner of the one room where man, wife and small child slept, ate, watched TV and listened to Beatles records but where, Ringo insisted, there was plenty of room for me to spend the night.

As in most Mongolian homes, there was a picture of Genghis Kahn on the wall But here the great warrior had to compete with John Lennon and Paul McCartney, whose images smiled down as their recordings came on full blast after Ringo apologized for not having any good recordings of his own group. Also as in every Mongolian home, there was plenty of vodka, and it was impossible to keep up with the toasts, each of which was punctuated by the traditional Mongolian gesture of dipping thumb and third linger into the glass, raising them above the head and sprinkling three times in praise of heaven and mountains. Later in the evening, the man on the ten-speed stopped by with a friend to help praise heaven and mountains and once more admire my bike and water bottles. T promised to mail him a bottle from the United States.

Between Darkhan and Ulan Bator, I spent a night at a communal farm village, left over from the economic system of a not-so-distant past. News of an English speaker checking into the small hotel travelled fast, and I soon was visited by the director of the local school. In excellent English, Mr. Ganbold said I was the first Westerner who had stopped during his ten years there. Two years ago he would no more have believed that, in 1991, an American would register at the hotel than that the Soviet Union would collapse.

A safer prediction is that, if Mongolia sticks to its open-door policy the coining years will find American and European bikers lined up at the roadside ice cream stand Ganbold and his wife are thinking of opening.

*****

In 1991, Peter Richards took early retirement from being a physicist in Albuquerque to devote more time to cycling.

Bike China Adventures, Inc.

Home | Guided Bike Tours | Testimonials |

| Photos | Bicycle Travelogues

| Products | Info |

Contact Us

Copyright © Bike China Adventures, Inc., 1998-2012. All rights reserved.